Forced Displacement on the Rise

At the end of June 2024, UNHCR recorded 122.6 million people worldwide who were forcibly displaced due to persecution, conflict, violence and human rights violations.[1] This number implies that 1 in 67 people worldwide suffered displacement, almost double the figure of 1 in 114 people which was recorded a decade before. This increase in forced displacement follows a steep upward trend in global conflict and violence, which is estimated to have doubled over the last five years, especially driven by conflicts in Ukraine, Palestine, Myanmar, Sudan, Mexico and Yemen.[2]

Almost 60% of the forcibly displaced population – approximately 72.1 million individuals – were forced to leave their houses and origin communities but have not crossed the borders of their origin countries, remaining there as Internally Displaced People (IDPs). The remaining 40% have moved to other countries – often neighbouring ones – and live there as asylum seekers and refugees. This latter number includes 32 million refugees and 5.8 million other people in need of international protection under UNHCR’s mandate, as well as 6 million Palestine refugees under UNRWA’s mandate.

Since forced movements often cover relatively short distances, the vast majority of displaced people (87%) live in low- and middle-income countries, which is where most forced displacement flows are generated. According to the latest figures available, Europe hosted 13.2 million refugees (10.7% of the worldwide population of forcibly displaced people) in 2024, with Turkey having the largest refugee population (3.1 million), followed by Germany (2.6 million), the Russian Federation (1.2 million) and Poland (0.9 million). In addition, 1.4 million asylum seekers had reached a European country to apply for refugee status.

The arrival of refugees presents specific challenges that add to the already complex task of integrating the broader immigrant population into host countries. In a world that appears to be moving further away from peaceful coexistence, it is reasonable to anticipate that the upward trend in forced displacement will persist — calling for careful analysis and innovative policy responses.

The Challenges of Integrating Immigrants

A recent OECD-European Commission report highlights substantial progress in the integration of immigrants across several dimensions in OECD countries (OECD-EC, 2023). Over the past decade, both the labour market integration of immigrants and the educational outcomes of their children have improved. Between 2011 and 2021, employment rates among recent arrivals increased in more than two-thirds of OECD countries, a trend partly attributable to their higher levels of educational attainment compared with previous cohorts. In 2020, nearly half of recent immigrants in the OECD had attained tertiary education, compared with less than a third a decade earlier.

Despite these important improvements, successfully integrating immigrants into societies and labour markets remains a key challenge for governments of host countries across the globe. Indeed, migrants in most destination countries continue to exhibit lower employment rates than comparable native-born workers, remain disproportionately exposed to unemployment and are heavily concentrated in precarious and low-paid occupations. While these disparities tend to diminish with longer-term stays in the host country — and even more markedly across generations, since second-generation immigrants generally achieve better socioeconomic outcomes than their parents — significant gaps persist. Notably, there appears to be little progress in improving the living conditions of immigrants and their children, who continue to experience poverty at rates considerably higher than those of the native-born population, with no clear downward trend evident (OECD-EC, 2023).

In Europe, a large body of research has shown slow and incomplete economic integration of immigrants, especially those with low education and coming from outside of Europe. Indeed, while EU migrants’ performance in EU labour markets closely resembles that of native citizens, a sizeable gap can be observed for non-EU migrants. In 2023, the employment rate was around 76% for both native citizens and EU migrants, dropping to 63% among non-EU migrants. In the same year, the unemployment rate was lowest among nationals (5.4%), with higher rates for citizens of other EU countries (6.9%) and much higher for non-EU citizens (12.2%). Beyond having higher employment rates and lower unemployment rates, EU migrants tend to secure more qualified and better-paid jobs compared to non-EU migrants. Still, both migrant groups experience substantial occupational downgrading, and EU migrants perform only marginally better than non-EU migrants in this respect.

Additional Challenges for Refugees

Refugees represent a particularly vulnerable population due to the additional challenges caused by their displacement, trauma and potential loss of human capital during their journey to safer countries. Unlike other migrants, refugees are often not positively selected in terms of education and skills and typically come from countries with cultural norms and traditions that differ significantly from those of the host nations. These factors contribute to a greater skill disadvantage and a higher risk of discrimination. Additionally, a key distinction between migrant and refugee flows lies in the different nature of these migratory movements. Migration is generally gradual, planned,and dispersed across multiple destinations, while forced displacement occurs in sudden waves, concentrated in a limited number of destination countries over a short period. This concentration in time and space intensifies the challenges associated with refugee integration.

Refugees represent a particularly vulnerable

population due to the additional challenges

caused by their displacement, trauma

and potential loss of human capital

during their journey to safer countries

Indeed, the fact that the labour market performance of refugees in European countries is significantly weaker than that of comparable non-EU migrants is well-documented in the academic literature (Brell et al. 2020). Fasani et al. (2022) estimate that refugees in EU countries are 11.6% less likely to have a job and 22% more likely to be unemployed compared to other migrants with similar individual characteristics. Additionally, refugees tend to have lower income, poorer occupational quality and lower labour market participation. These disparities persist up to 10-15 years after arrival in the host countries. These large and persistent gaps represent a clear call for action.

Key Barriers to the Labour Market Integration of Migrants and Refugees

Labour market integration of migrants and refugees is just one element of their broader social, political and cultural integration in hosting societies, but it is often seen as a necessary condition for observing significant progress in all other areas. If we define economic integration as the extent to which migrant workers will achieve the same depth of labour market integration as native citizens by fully using their skills and realizing their economic potential, we can think about barriers that prevent migrants from reaching such a target.

Integration barriers can affect several margins of migrants’ labour market outcomes. First, they may discourage migrants from participating in the labour market and actively looking for a job, reducing their participation rate. Second, they may reduce the probability of finding employment for those who are searching. Third, integration barriers may constrain the number of hours and the stability of employment relationships for migrants, confining them to undesired part-time and temporary occupations and hence leading to underemployment. Finally, barriers can reduce the quality of employment, leading to jobs in the informal market, with low pay, poor working conditions, little recognition of workers’ qualifications, etc.

A Taxonomy of Key Barriers

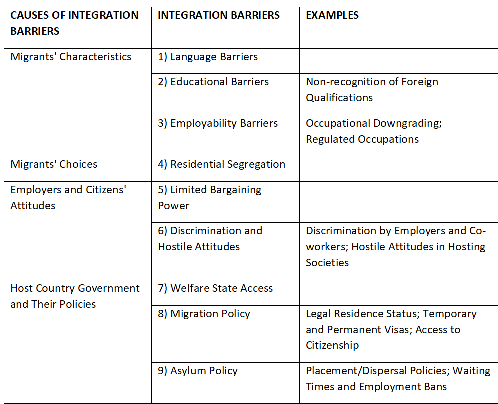

Fasani (2024) proposes a taxonomy of the main integration barriers faced by migrants and refugees in hosting societies which groups them into nine major categories and attributes them to broader causal factors, as reported in Table 1.

TABLE 1 Key Integration Barriers and Their Causes

First, we can identify three barriers arising from migrants’ characteristics (e.g. their human capital) and their match with labour demand in destination countries:

(i) Language barriers: Limited knowledge of the host country language poses a serious challenge, since fluency is a crucial skill that complements the existing abilities of migrants and refugees, unlocking better educational and occupational opportunities for them in host countries;

(ii) Educational barriers: Educational qualifications obtained in source countries are often valued far less by host country employers than those acquired in destination countries, since the former are often not – or only partially – recognized, leading to pervasive skill downgrading among migrants;

(iii) Employability barriers: Lack of knowledge of the host country labour market – coupled with the existence of regulated occupations whose access is often prevented to migrants – may severely hinder the effectiveness of migrants’ job seeking efforts, leading to unemployment and discouragement.

Second, migrants’ choices – residential choices, in particular – may generate important barriers. Migrants display a tendency for residential segregation, settling in areas with established communities from their region or country of origin. While these choices can improve their wellbeing – and, in certain cases, also their economic outcomes – in the short term, effects in the medium and long run may be detrimental, if residential segregation reduces host country language acquisition, educational investment and interactions with native workers.

Third, further barriers and delays to economic integration can be created in the interaction with host country’s employers and citizens if migrants are met with discriminatory practices, widespread misperceptions and general hostility, which may further weaken their bargaining position in the labour market, leading them to accept substandard working conditions and wages.

Finally, important barriers can be generated by the interaction with the policies implemented by host country governments. First, by regulating access to the welfare state, host country governments can reduce migrants’ exposure to income instability and poverty risk, allowing them to pursue training and job opportunities that enhance their long-term employment prospects. Second, the migration policy framework defines key areas of the migrants’ experience and integration, such as access to legal residency status, permanent residency and citizenship. Third, asylum policy – by defining key aspects such as the geographical allocation of refugees, waiting times for refugee status recognition and access to the formal labour market – can shape the economic integration of asylum seekers and refugees.

Refugee-Specific Barriers

All integration barriers described above – but for the very last group (i.e. those potentially created by the asylum policy) – typically affect both migrants and refugees in host countries’ labour markets, although the forced and unplanned nature of refugee migration can further exacerbate the negative impact of these barriers for refugees. The asylum policy could effectively reduce the initial disadvantage refugees inevitably experience relative to other migrant groups who arrived in host countries for other reasons (work, study, family reunification, etc.). Indeed, this regime provides significant rights and entitlements – such as income and housing support – available to all asylum applicants, with additional provisions for those who successfully attain refugee status. However, the asylum system can also introduce further barriers to integration, as clearly demonstrated by the literature which has studied these policies. In particular, it has been shown in several contexts that displacement policies – which aim at allocating and housing asylum seekers and refugees in different areas of the host country – often place them in undesirable locations with limited employment opportunities, further delaying their integration process. Similarly, long waiting times for refugee status determination have been shown to persistently reduce employment rates of affected claimants. Finally, the widespread practice of imposing temporary employment bans, preventing asylum seekers from legally accessing the formal labour market, can also generate long-lasting reductions in Refugees’ employment and labour market participation (Fasani et al, 2021).

All integration barriers affect both migrants

and refugees in host countries’ labour markets,

although the forced and unplanned nature

of refugee migration can further exacerbate

the negative impact of these barriers for refugees

Policy Implications and Conclusions

The policy interventions implemented to tackle the integration barriers described above are highly heterogeneous across countries and over time. While the quantitative evaluations of their effects have often reached ambiguous and contradictory conclusions, there seem to be a few general policy lessons that seem to attract wide consensus among experts and practitioners. In particular:

- Focus on the period immediately after arrival: Early interventions soon after arrival have stronger and more lasting impacts on migrants’ integration paths than policies implemented later on;

- Identify and balance trade-offs in policy interventions: Each policy measure can potentially entail some trade-off, whereby the migrants and refugees involved in the intervention gain on some integration dimensions, but lose on others;

- Remove unnecessary integration barriers: Some barriers created by migration and asylum policies – such as the obstacles to recognition of foreign qualifications or employment bans for asylum seekers – generate no desirable effects and delay migration integration;

- Reduce uncertainty faced by migrants in host countries: Protracted uncertainty about their status in the host country – such as regarding visa renewal or obtaining citizen status – is detrimental to migrants’ economic integration.

Successful integration bolsters migrants’

economic contributions to host societies

by fostering greater labour market participation

and reducing reliance on welfare support

Policymaking in the field of migrant economic integration should be guided by these general principles, alongside a clear understanding that the benefits of integration extend well beyond the migrants themselves. Enhanced integration significantly improves the well-being of migrants and refugees, as well as that of their children and extended families. These improvements, in turn, generate positive spillover effects for communities and families in countries of origin, through financial remittances and the transmission of social norms and practices. Furthermore, successful integration bolsters migrants’ economic contributions to host societies by fostering greater labour market participation and reducing reliance on welfare support. There is, therefore, a compelling economic rationale for investing in the integration of migrants and refugees.

References

Brell, C.; Dustmann, C. and Preston, I. “The labor market integration of refugee migrants in high-income countries.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 34(1), 94–121, 2020.

Fasani, Francesco; Frattini, Tommaso & Minale, Luigi. “Lift the Ban? Initial Employment Restrictions and Refugee Labour Market Outcomes.” Journal of the European Economic Association, European Economic Association, vol. 19(5), pages 2803-2854, 2021.

Fasani, Francesco; Frattini, Tommaso & Minale, Luigi.”(The Struggle for) Refugee integration into the labour market: evidence from Europe.” Journal of Economic Geography, Oxford University Press, vol. 22(2), pages 351-393, 2022.

Fasani, Francesco; Frattini, Tommaso & Pirot, Maxime. “From Refugees to Citizens: Labor Market Returns to Naturalization.” CEPR Discussion Papers 18675, 2023.

Fasani, Francesco. “New Approaches to Labour Market Integration of Migrants and Refugees.” Committee on Employment and Social Affairs, Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, European Parliament; 2024. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/17908701/new-approaches-to-labour-market-integration-of-migrants-and-refugees/18804512/.

OECD-EC, Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2023, OECD – European Commission, 2023. www.oecd.org/en/publications/2023/06/indicators-of-immigrant-integration-2023_70d202c4.html.

[1] Source: UNHCR, link: www.unhcr.org/mid-year-trends.

[2] Source: ACLED, link: https://acleddata.com/conflict-index/.

Header photo: Workers on a construction site. Orascom Construction Industries (Airport Tower). Orascom Construction Industries (OCI) is a leading construction contractor active in emerging markets. Based in Cairo, it employs more than 40,000 people in over 20 countries. Marcel Crozet / ILO CC BY-NC-ND 2.0