The Middle East and North Africa is a “penetrated region,” where China is a relative latecomer, arriving at a time when the end of the Cold War and the consequent “unipolar moment” of the US have been followed by the complex, complicated and still ongoing transition to a post-American regional order. While the US, in spite of its declared aim to turn away from and pay less attention to the MENA region, cannot disengage from it, other external actors, among them China, but also Russia, the EU and potentially others, too, are increasingly formulating interests of their own. Thus, the Middle East and North Africa region has become a “proxy stage,” where China has to articulate its interests not only vis-à-vis the United States, but also against – or eventually in cooperation with – other external actors.

This goes hand in hand with a new regional order in the making, in which how the final balance of power is going to stabilize is still not clear. The order among the Arab states has undergone a profound change: former Arab nationalist and/or socialist leaders (Egypt, Iraq, Syria), due to different reasons, have weakened; the Arab unity front has split, due to its inability to successfully represent rare, all-Arab consensus interests on the international fora (Palestine, concern over Israel’s nuclear capability); Gulf Arab states have started to intervene in the political and security processes of other Arab states on the basis of their financial support. Different capabilities, political systems, threats such as migration, terrorism, or the Israeli and/or Iranian nuclear programme, have further accentuated the increasingly divergent developments in the Arab states. This became evident in the Arab Spring and the fight against the Islamic State, but also in the sub-regionalization of Arab attention: the Maghreb increasingly turning towards the Sahel, Egypt’s focus on the Nile valley and the Gulf (some Arab Gulf states) coming closer to Israel, while at the same time in a “Cold War” with Iran. In parallel, an increasingly assertive Turkey presents a military and ideological/religious challenge. Israel is quietly and slowly trying to integrate in the region and, with US support, has concluded the Abraham Accords with several Arab states. Iran, in spite of the harshest sanctions ever, is affirming its regional power status and has established an allied network of non-state actors.

This fragmentation of the region suits China’s tendency to not perceive the Middle East and North Africa as one unit, and fits its practice of maintaining bilateral relations with the regional states, instead of a regional approach.

Chinese Relations in the Middle East and North Africa

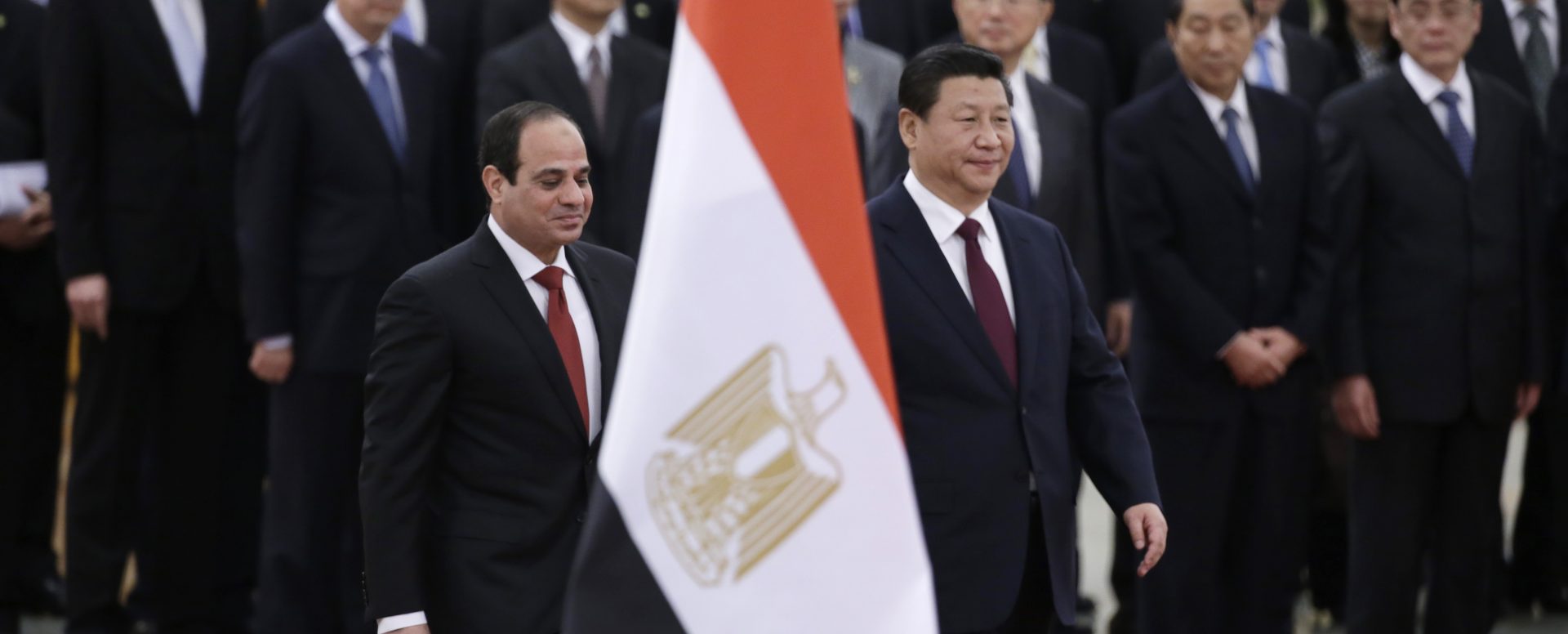

The Middle East and North Africa has traditionally been outside of China’s sphere of interest – rather, based on the ancient Chinese world view of concentric circles, it has been the western hinterland to its western periphery. Geographical distance, loose historical contacts, social, cultural and linguistic differences, etc, have all contributed to this perception. Consequently, the rapidly developing, wide variety of relations China has established throughout the MENA region are relatively new. They also reflect both the international context and China’s inner developments, and thus may be very different from country to country regarding their underlying basis, scope and extent. While the “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence” formulated by Chinese premier Zhou Enlai are valid to this day, especially non-intervention and non-interference, the earliest relations were concluded on the platform of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), with China’s non-aligned status, communist internationalism and the rejection of imperialism as the underlying ideological common ground. The first diplomatic relations were established with Egypt in 1956, followed by Algeria, Iraq, Morocco, North Yemen, Syria and Sudan in the same year; then by Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya and Tunisia, all of which became members of the NAM in the 1960s. These principles defined China’s stance towards two of the main developments in the MENA region at the time: decolonization and the Arab-Israeli wars. In the early 1980s, upon Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening-up policy, China started to look for new partners who could satisfy the rapidly increasing need for energy resources, and hence the states of the Persian Gulf came into China’s focus of attention. Securing stable and continuous supplies then became and has remained a top priority on China’s foreign and security policy agenda. Although Deng Xiaoping’s “low profile” policy still seems valid, at least to a certain extent in China’s MENA relations, the new policy launched by Xi Jinping brings China “closer to centre stage and makes greater contributions to mankind.”

This Chinese evolution, based on and backed up by rapid Chinese economic growth, resulted in – among others – an enhanced self-confidence, a new economic outreach to wider regions and to a Chinese presence farther away from China’s traditional neighbourhood. The “pivot to Asia” announced by President Barack Obama, the “looking to the east” policies both in Europe and the MENA region, as well as the increasing reluctance of Western states to get involved in the transition and conflicts of the MENA region was the context to China’s “march west” policy and the consequent launch of the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013.

The Belt and Road Initiative

While originally the Belt and Road Initiative (Silk Road; One Belt, One Road; BRI) was launched to connect China to Europe, both over land and over sea, it practically avoided, or rather left the Middle East and North Africa untouched (Land routes included Iran and Turkey, while the maritime route was planned to pass the Red Sea from the Bab el-Mandeb to the Suez Canal, but with relatively little attention in the original plans to littoral states). By 2021, however, most of the states of the region have been included in some way in the project, many out of their own initiative. China’s relations to the countries in the Middle East and North Africa, consequently, are very different in content, make up a hierarchical order with several different “partnerships,” and, due to the evolving nature of the BRI, are in a state of continuous change.

The BRI especially focuses on the development of infrastructure, providing for and enhancing connectivity, including ports, roads and railways. Its implementation entails Chinese capital and loans, Chinese technology, Chinese companies and even Chinese labour, raising tensions in some places and contributing to local development in others. (It should be noted, however, that the BRI is complemented by other connectivity projects with Chinese participation, e.g. the String of Pearls, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, CPEC.)

The hierarchy of the relations builds up within three main categories (or levels): strategic partnerships, comprehensive strategic partnerships and potential partnerships. Besides these, specific partnerships can also be concluded. It is indicative that China has “comprehensive strategic partnerships” with Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and “strategic partnerships” with eight others. With Turkey, China has concluded a specific “comprehensive cooperative partnership,” and with Israel a “comprehensive innovative partnership.” (It should be noted, however, that these relationships are not alliances, as, historically, China shies away from concluding alliances.)

The China-Iran Deal

In March 2021, the news of a 25-year, 400-bn US$ China-Iran cooperation agreement made the headlines. The agreement was signed during a visit to Tehran by China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi, and from the Iranian side by Ali Larijani, personally appointed to the task by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. While no details have officially been published, leaked information reveals agreements on energy, infrastructure, economic, trade and military cooperation (joint naval exercises have been held before), which includes the fight against terrorism and extremism in the region. It is still unlikely that China would sell Iran military equipment of strategic significance before the nuclear negotiations come to a conclusion, in spite of the fact that the arms embargo imposed on Iran in the JCPOA terminated in 2020.

Even with the wide-scale and intensive cooperation between the two states foreseen in the deal, it seems more like a complement to the “comprehensive strategic partnership” agreement concluded in 2016, than anything substantially new. As such, it also remains to be seen if, when implemented, it exceeds the other “comprehensive strategic partnerships” China concluded with Algeria, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. It should be noted, however, that, besides the international debate, the deal has become the target of fierce criticism within Iran as well: many claimed that against US and Western hostility, Iran should turn east; others warned that the Islamic Republic should not give up its sovereignty and become subservient to China.

China’s Security and Military Engagement

China’s presence in the Middle East and North Africa has increasingly been analysed in the context of US-China competition, usually maintaining that China eventually would (or would want to) take over the US’s position, but noting that for the time being China seems happy to let the US be the security provider in the region. China’s security engagement in the region now and in the near future is limited, and seems to hold that “development comes before security in promoting stability.” This is the result of several different factors, besides the principles of non-interference and non-intervention, including economic needs and China’s military capabilities, which limit the country’s military power projection to its immediate neighbourhood. However, most analyses contemplate that the defence of Chinese interests, investment and Chinese labour (human capital) will, sooner or later, make it necessary to further expand Chinese security and military engagement. The undergoing development of Chinese military capabilities (blue-water navy, 5th generation tactical aircraft, longer range planes) suggests that such a scenario in the mid to long term cannot be ruled out, and the first Chinese military base in the region, in Djibouti, is often described as a step in this direction.

Chinese security engagement in the region so far has been manifest in non-military activities such as arms trade, evacuation of citizens, humanitarian relief, search and rescue operations, peacekeeping and conflict prevention missions – and as such, China is presenting itself as the responsible global power, supporting the multilateral character of the international order. Although China is now the second largest arms producer and the fifth largest exporter globally, its share in the arms trade to the Middle East and North Africa is relatively limited as the bulk of its arms exports (82%) is directed to Asia.

China’s participation in UN peacekeeping missions, especially from the beginning of the 2000s, has increased, providing some 2,500 troops and police officers, of which in 2020 approximately 800 troops were serving in Sudan (Darfur) and Lebanon. In addition, China’s participation in anti-piracy operations, to protect merchant vessels from pirates in the Gulf of Aden, has been an especially noteworthy element, because China’s deployment of some ten thousand navy personnel from 2008 onwards marked the first time naval forces had operated beyond China’s immediate maritime periphery for extended durations.

Chinese Soft Power: Culture and Vaccine Diplomacy

The MENA region has historically been more accustomed to Western cultural norms and values, making China somewhat disadvantaged in its dealings with the region. In spite of the increasing awareness of China and its role, mostly in the context of the expanding Belt and Road Initiative, the appeal of Chinese soft power among the public in the MENA region has remained relatively limited. Yet, the physical presence of Chinese people, either as workers on BRI-related projects or as students, is increasingly visible, albeit potentially very different from country to country. (The biggest community lives in the UAE, which has a Chinese population of around 300,000.) Another factor increasing Chinese visibility in the MENA region has been the growth of Chinese tourism to the region, in spite of the fact that the Middle East and North Africa was not among the top ten tourist destinations for the Chinese (before the pandemic). Chinese soft power activities have included the establishment of Confucius Institutes in the MENA region (in 2020 there were 23 of them altogether) to promote Chinese culture, and China has offered a wide range of scholarships for students to carry out their studies in China.

The COVID-19 pandemic, by the very fact that it originated from China, had a direct negative impact on China’s image in the MENA region, to the extent that there was perceivable resentment against Chinese communities living in the region. Indirectly, the pandemic and the consequent lockdowns and travel restrictions affected Chinese tourism to the Middle East and North Africa, and also had an impact, albeit as yet unclear, on student movements and probably on the operation of the Confucius Institutes as well.

Yet, with its indigenous vaccines developed, China has launched a successful vaccine diplomacy campaign towards, among others, the Middle East and North Africa (in which Russia, and potentially others as well, has become a competitor). The Health Silk Road originally proposed by China in 2017 has thus materialized as a complement to the BRI, with vaccine diplomacy as its most accentuated element.

Yet, China’s reputation and perception in the Middle East and North Africa, as well as the wider Islamic world, has been tested in recent years, over the situation of the Muslim Uighur minority in China. While commonly conceptualized by China as an “Islamic threat” and a “case of terrorism,” bearing in mind all BRI tracks cut through mostly Muslim countries (or countries with sizeable Muslim communities), the Uighur question carries a huge potential for disruption. Yet, MENA states (except for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan) have, as a rule, kept a low profile when Chinese treatment of its Uighur citizens has been widely presented in the international media, and even blocked a Western motion at the UN calling for China to let independent international observers visit the Xinjiang region.

China in the UN Security Council Rotating Presidency

In May 2021, China took over the rotating presidency of the UN Security Council. This role gave China the chance to portray itself as a responsible superpower and helped promote China’s vision of multilateralism. China, with no colonizing past, but instead a victim of colonization itself (“century of humiliation”), to this day positions itself as a developing state and has advocated the reform of the UN Security Council to change the uneven representation of Western states there. Chinese competence, however, was put to the test when, in May 2021, the Hamas/Palestinian-Israel conflict hit the UN Security Council agenda and demanded urgent action.

The Hamas/Palestinian-Israel Conflict

China’s support of the Palestinians reaches back to the Cold War and its support of national liberation movements. China abstained from voting on the UN Partition Plan on Palestine and supported the Palestinian right of return. In 1988, together with the socialist countries, it also recognized the declaration of the State of Palestine. China-Israel diplomatic relations, however, were only established in 1992, in spite of the fact that in the MENA region, Israel was the first country to recognize the People’s Republic of China in 1950. As a consequence, in recent decades, China has been among the very few countries to maintain good relations with both the Palestinians and Israel. This policy of “not taking sides” was challenged by the Hamas-Israel confrontation.

In spite of the fact that the eleven-day-long rocket exchange and aerial operations between Hamas (from the Gaza Strip) and Israel looked as if it was “business as usual” (in spite of the fact that the last such confrontation took place in 2014), many things have changed in the background: 1. A political crisis is prevailing both in Israel and among the Palestinians; 2. Israel’s Arab citizens stood up together with the Arab residents in Jerusalem and the Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip; 3. There has been a shift in the global perception of the Palestinian cause, especially in the US, where domestic developments over Floyd George last year have changed the US public’s perception of civilian resistance, and where a group of Democratic Congressmen and women started to push President Joe Biden over his human rights programme; 4. All this put the Palestinian issue back on the international agenda, from where it had practically disappeared, and forced China, in its position as the President of the UN Security Council, to act.

The crisis between Israel and Hamas provided China with the opportunity to not only present itself as a non-biased mediator, but, at the same time, portray the United States as a biased actor, bringing a different context and interpretation to the issue.

The importance of both dimensions (China as a responsible global power in its role as the President of the UN Security Council and China-US competition) was reflected by the fact that – following two rounds of consultations – the open debate on The Situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian Question was chaired by Chinese State Councillor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi, who put forward China’s four-point proposal on the settlement. While the content was not new (the proposal was in fact a repetition of similar former calls) and generally reflected the international consensus, it seemed to again confirm China’s general non-aligned position. It called for a two-state solution based on the 1967 borders (“a fully sovereign and independent Palestinian state … with East Jerusalem as the capital, to achieve the harmonious existence of the Arab and Jewish nations and lasting peace in the Middle East”), the condemnation of human rights violations and mediated negotiations, to which China offered its services. Wang also called for the immediate cessation of military actions, the lifting of the Gaza Strip’s blockade and delivery of humanitarian aid. Yet, when Wang named Israel (“Israel must exercise restraint in particular”), but did not mention the rockets fired from the Gaza Strip to Israel, China’s position as an unbiased neutral mediator was brought into question both by Israel and the United States.

When the United States blocked the joint resolution, China took its chance to criticize the “only country” responsible for the failure, and accused the United States for its one-sided support to Israel and for disregarding the humanitarian concerns in Gaza. With that, China also tried to divert political and media attention away from criticism over its treatment of its Uighur minority in Xinjiang.

The direct and indirect consequences of China’s role are yet to be seen. Nevertheless, China’s position, based on the international consensus of recent decades, seems to be a suitable foreign policy tool to maintain the balance between China’s relations with both Israel and the Arab states. This, in turn, will serve China’s position well both in the context of US-China relations and, more specifically, in the Middle East and North Africa.

Bibliography

Csicsmann, László;N. Rózsa, Erzsébet and Szalai, Máté: “The Mena Region in the Global Order: Actors, Contentious Issues and Integration Dynamics.” MENARA Methodology and Concept Papers, No. 4, 2017. http://menaraproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/menara_cp_4.pdf

Deng Xiaoping: “Observe calmly; secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide our time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership.” Deng Xiaoping quoted in: Office of the Secretary of Defense, Military Power of the People’s Republic of China: A Report to Congress Pursuant to the National Defense Authorization Act Fiscal Year 2000, Washington, 2008, https://fas.org/nuke/guide/china/dod-2008.pdf

Figueroa, William: “Can China’s Israel-Palestine Peace Plan Work?” The Diplomat, 25 May, 2021. https://thediplomat.com/2021/05/can-chinas-israel-palestine-peace-plan-work

Fulton, Jonathan, “China Is Becoming a Major Player in the Middle East,” Brink News, 19 September, 2019, www.brinknews.com/china-is-becoming-a-major-player-in-the-middle-east/

Fulton, Jonathan: “China’s Changing Role in the Middle East.” The Atlantic Council, 2019, www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Chinas_Changing_Role_in_the_Middle_East.pdf

Lons, Camille; Fulton, Jonathan; Sun, Degang; Al-Tamimi, Naser: “China’s Great Game in the Middle East.” ECFR Policy Brief, October 2019, https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/china_great_game_middle_east.pdf

Makdisi, Karim; Hazbun, Waleed; Senyücel Gündoǧar, Sabiha and Dark, Gülşah: “Regional Order from the Outside in: External Intervention, Regional Actors, Conflicts and Agenda in the Mena Region.” MENARA Methodology and Concept Papers, No. 5, November 2017. http://menaraproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/menara_cp_5-1.pdf

N. Rózsa, Erzsébet: “Deciphering China in the Middle East,” EU ISS Brief, 2020, www.iss.europa.eu/content/deciphering-china-middle-east

NSD-S HUB: China’s Relevance in the Security Domain in Africa and the Middle East. June 2020. thesouthernhub.org/publications/nsds-hub-publications/chinas-relevance-in-the-security-domain-in-africa-and-the-middle-east

Propper, Eyal: “China, the United States, and the Gaza Crisis: Israel for Xinjiang?” INSS Insight No. 1472, 25 May, 2021. www.inss.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/no.-1472-1.pdf

Sidlo, Katarzyna (ed): “The Role of China in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Beyond Economic Interests?” EuroMeSCo Joint Policy Study 16, 2020, www.euromesco.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/JPS_The-Role-of-China-in-the-MENA.pdf

Soler i Lecha, Eduard; Colombo, Silvia; Kamel, Lorenzo and Quero, Jordi: “Re-Conceptualizing Orders in the MENA region. The analytical framework of the MENARA Project.” MENARA Methodology and Concept Papers, No. 1, November 2016. http://menaraproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/menara_cp_1-4.pdf

United Nations Situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian Question – Security Council VTC Open Debate. 16 May 2021,www.unmultimedia.org/avlibrary/asset/2619/2619227/

Wang, Jisi: “‘Marching westwards’: The Rebalancing of China’s Geo-Strategy.” ISS Report no.73, 7 October, 2012. Center for International and Strategic Studies,